Sapiens or “How I Decide to Read a Book”

For a while now people have been recommending the book “Sapiens.” So I looked it up. As I glanced over it I realized I that I have a methodology and order for how I grade a book before I decide to read it. Here is the process I go through in order to decide whether or not to read a book. In this case, Sapiens.

First, I look at the title.

The title is “Sapiens: a brief history of humankind.” Already I see a narrative being presented in the title: sapiens means humankind. The Homo genus is actually what “humankind” means. So this title is misleading and inaccurate, in that it’s seemingly setting up a framework to only discuss the last 200,000-300,000 years of our species, and not any of our human ancestors. Also, within paleoanthropology and evolutionary theory, the distinctions between the different Homo species are blurring and becoming somewhat meaningless, but I will get to that later. The title already has me immediately turned off, but not enough to not read the book. (To the authors credit, he does mention later that term “human” refers all the way back to Homo habilis, some 3 million years–but my point still stands).

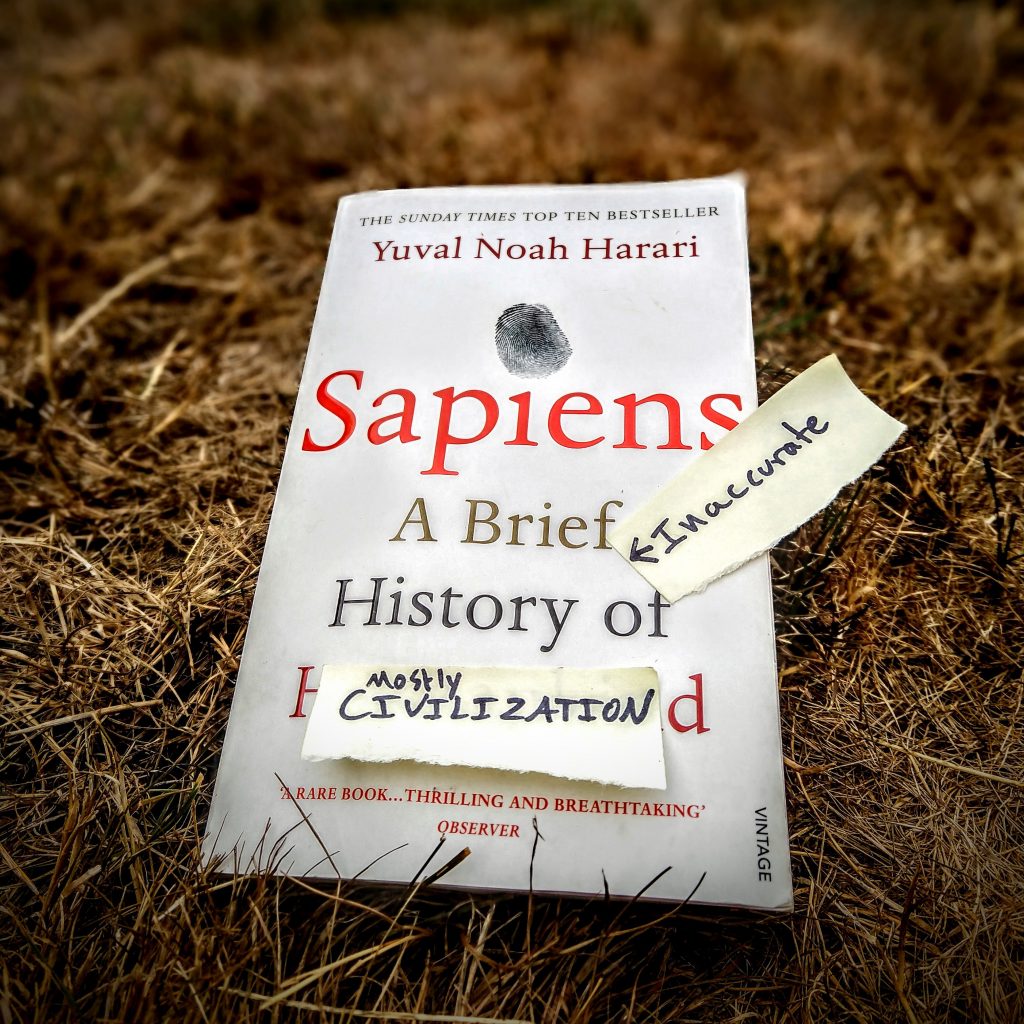

Then I examine the cover.

The cover is bland enough to not steer me away, nor pull me in. I try not to judge a book by its cover, but “less is more” for me, and they do a good job of that. The one thing I notice is across the top it says, “The Sunday Times Top Ten Bestseller” and I’m immediately under the impression that this book doesn’t challenge any of the standard narratives of civilization. Anything that is a bestseller is usually something that reinforces our beliefs, not questions or dispels them. Again, this is a red flag for me, but not enough to not read the book.

Then I read the jacket.

The Jacket is the real point that can be the deciding factor on whether or not I think a book will be worth my time. Often the jacket is not written by the author, and isn’t wholly reflective of the content within the book. It can also be intentionally used to trick people to read the book, a sort of “bait and switch.” The jacket of Sapiens felt pretty horrible to me. Here is my breakdown, line by line.

100,000 years ago, at least six human species inhabited the earth. Today there is just one. Us. Homo sapiens.

This is super misleading and inaccurate on multiple levels. The idea of what a species is, is rapidly changing both within paleoanthropology and within evolutionary theory itself. We’re starting to realize that the many different “species” of the Homo genus are most likely just one species: Homo erectus (including us). This is because variation within a species is huge, and that was never taken into account. Previously, when paleoanthropologists discovered each new Homo skull with different morphology, they would classify it as a whole new species. Due to recent discoveries (5 skulls with different morphology found in the same context) they had to rethink this. After doing a cross analysis of modern humans, they found the variation in morphology to match the same as all the different morphologies within the paleoanthropological record. This means that there wasn’t really all these different species, but just different variations of humans in the same way that we see today. Diet, environment, genetics all play roles in the development of our bones. It’s also weird that they say 100,000 years ago, almost implying that Homo sapiens came about at that time. Even if you follow the old narrative of multiple Homo species existing at the same time, Homo sapiens date back to around 300,000 years ago. A more contemporary sentence would read like this, “Ten years ago we thought there used to be dozens of human species, today we’ve realized that there has always been just one.” The next sentence plays off the inaccuracies of the first and adds to a false narrative.

How did our species succeed in the battle for dominance?

There are three cultural narratives slipping past folks in this statement. One: that there were different human species (we now presume there weren’t). Two: that they were in competition against one another–and that Homo sapiens “won” a “battle” by virtue of all other Homo species being “extinct” in the present era. Three: that this perceived “domination” means “success.” Once we see that the species delineation is more complicated, the implications behind questions like this are much more easily dismissed. If our species variation’s are more fluid, then they are about adaptation and collaboration, not “competition.” Not to say that competition between species doesn’t exist, but that cooperation is an equally viable strategy (often times more viable) in terms of these cultures of humans blending back together. The best example of this is the classic Neanderthal vs. Homo sapiens narrative; the theory that Homo sapiens “wiped out” the Neanderthals. Through DNA testing and mapping of the genome, we know that modern humans who have a genetic history of migration out of Africa actually share genes with Neanderthals. This means that Neanderthals didn’t “go extinct,” and they weren’t “wiped out.” It means they hybridized with Homo sapiens. One did not destroy the other, they came *back* together. A contemporary example of this kind of thing is happening right now with the eastern coyote. When their DNA was tested, it was found that they were very high in wolf DNA, and also some domestic dog DNA. Wolves and Coyotes branched away from another some 200,000 years ago, and yet they are still able to have viable offspring. They fill completely different ecological niches, look very different, behave very differently, and yet they can have babies. For 200,000 years they diverged to specialize in different ecological niches–lessening their competition. But due to the environmental impacts from civilization, coyotes have adapted to these changes through hybridization with wolves and domestic dogs. This brings up two important points: that the species differentiation could have happened as a way of lessening competition (two different species filling two different niches are not in as much competition) and the hybridization shows a lack of competition, but cooperation to adapt in the face of environmental change. The concept of interspecies competition and “dominance” in evolution is just one small part of a whole range of interactions and set of strategies. The DNA of those whose ancestors migrated out of Europe are not exactly “Homo sapiens,” they are hybrids. We are all hybrids. That is one of the reasons the species distinction is making less and less sense. This sentence from the back cover alone is enough to completely turn me away from this book. If it weren’t for people telling me to read it, I wouldn’t. Again, I’m banking on this jacket being of the “bait and switch” variety. The next line is…

Why did our foraging ancestors come together to create cities and kingdoms?

Another very problematic sentence immediately following the other. This makes it sounds like foragers had intention to create civilization. Humanity didn’t come together to create these things. The transition from foraging to agriculture was very slow and in small pockets. There was never any intention to create what we have today; the creation of kingdoms is a symptom of many things, but too long to discuss in a simple book review (Read my book Rewild or Die). In brief: immediate-return gatherer-hunters, for the most part, have rejected agriculture and pastoralism. They diffuse inequality and do not accumulate wealth. There is no myth of humanity’s “progress” nor a desire to do so. At this point it just sounds like I already know more than the author and that this book is either garbage with the same mythology of civilization, or a pop cultural book for people who don’t read up on contemporary paleoanthropology.

The rest of the back seems boring and generic and I don’t have anything to say or deconstruct. The inside though, have these words assembled together:

FIRE: Gave us power

GOSSIP: Helped us cooperate

AGRICULTURE: Made us hungry for more

MYTHOLOGY: Created law and order

MONEY: Gave us something we can really trust

CONTRADICTIONS: Created culture

SCIENCE: Made us deadly

This is the thrilling account of our extraordinary history – from insignificant apes to rulers of the world.

Right off hand I see the standard narrative of civilization all over this, and it makes me sick to my stomach. It’s also a word salad that could have been generated by an algorithm. You could almost take any of the sub sentences and mismatch them with any of the headlining words and they would sound interesting and thought provoking. Example:

FIRE: created culture… AGRICULTURE: made us deadly

That is absurd in and of itself, and I’m assuming these are actual connections that the author is going to try and draw in the text, but you could draw these connections to all kinds of things. The premise here that I take main issue with is the use of the word “us.” Blank made us blank. Agriculture, money, science… These things are not universal aspects of Homo sapiens or humanity. Here they have done what civilization has always done; conflated itself and its values with humanity. This tells me that it isn’t a book about Homo sapiens, it’s a book about Civilization and those who made it. This is the standard narrative and is one premise that most people don’t realize, or don’t find important. We want to believe that humanity did all of this. But the Bushmen didn’t. The Hadzame didn’t. The Apache didn’t. An accurate portrayal may be to say “some of us,” but clearly that isn’t definitive enough or grand enough to sell books to people who want to continue to believe that their way of life is the way of life for our species. Imagine a book called “Sapiens” from the perspective of the Bushmen living today. How would that narrative read? Maybe the jacket would read something like this:

GATHERING: kept the world living.

SHARING: made us connected.

LIMITED WANTS: kept us from accumulating wealth.

EFFICIENCY: gave us leisurely lives.

And so on. That’s the story I’m more interested in knowing, and the one that is more important now than ever. At this point, I know for sure I can’t read the whole book, but I’m going to continue with my process anyway.

Okay, now it’s onto the…

Quotes

When all the quotes come from the names of newspapers and not scientific peers, that’s another red flag to me that says, “Pop Cultural Bullshit.” This one had all newspapers, but one actual person’s name attached to the last quote… Jared Diamond. A known liar and unethical pop cultural writer who masquerades as an historian. The only quote with an actual name attached to it is someone discredited by the anthropology community. How many red flags is this so far? I’ve lost count.

Table of Contents

Once I get past the jacket, I open to the Table of Contents. Right away there is more narrative.

Part One The Cognitive Revolution

1 An Animal of No Significance

Okay. Here we go. This is a value statement. What is “significance?” Why not, “an amazing animal that lived for 3 million years within the flux of ecosystems, adapting and changing with it?” Unlike civilization, which is self-destructing within a mere 10,000 years. Is it not more “significant” to be a part of something for so long? Think about this. Think about how under this framework, cultures like the bushmen, or the hadzame (Since they have not changed dramatically in tens of thousands of years) are essentially being labeled as “animals of no significance.” Can you see the cultural narrative now? I can and it makes me actually feel physically gross.

Part Two The Agricultural Revolution

5 History’s Biggest Fraud

6 Building Pyramids

7 Memory Overload

8 There is No Justice in History

The rest of the table of contents seems innocuous and maybe a little interesting. There is one overall qualm though. It’s the amount of time spent on prehistory. For a book called Sapiens, you might think would cover the 300,000 years that Homo sapiens are thought to have been on the earth. But looking at the table of contents of these kinds of books about prehistory, the first 3 million years of the human story, or in this case of this book, the first 300,000 years is only given a small percentage of the book. An example is that this book has 4 sections. This means that, percentage wise, the first 290,000 years are all crammed into one section. The rest of the book is only about the last 10,000 years–the (mostly) written history of civilization. What this says to me is, to use the jacket’s own words, the first 300,000 years are “insignificant.” That’s probably one of my biggest pet peeves, and will no doubt be reflected in the rest of the book in more ways than one.

Through this deduction method, I don’t want to imply that I don’t read things that are “counter” to my way of seeing the world. That I can only live in some kind of echo chamber where I never question my own beliefs. This is not what I am saying. I do read things outside of my perspective; the majority of pop culture has not caught up with the majority of anthropology and paleoanthropology–from the 1970’s. Pop culture is 50 years behind science. I try to read as though I am an alien anthropologist studying humans. I try to decipher between what is being observed (and not observed), what is the story we are telling about ourselves–and why. What are the intentions of the story? Who does the story serve? This is what I find the most fascinating. But also, I’m an emotional creature and these myths have an emotional impact on me, so I have to watch out for that too.

People want to believe in the duality. That humans are either good or evil, and they seek out a story to justify their actions. If humans are inherently evil, then we shouldn’t feel all that guilty about destroying the planet. If humans are inherently good, then we believe this destruction is from having just taken a huge step in the “wrong” direction. For my part, I believe humans are not inherently anything, or they are inherently everything. Our environment dictates our culture, our culture dictates our actions. For 3 million years our environment dictated a culture, and that culture kept us in a regenerative relationship with the ecosystems we are a part of. Something changed in *some* of our environments, which triggered change in *some* of our societies, and in *some* of the actions within those societies that eventually created the global culture of State occupation and environmental degradation that we see today.

I research and learn about prehistory because I want to understand what these changes were so that I can figure out solutions to our problems. This means walking away from judgments of “good” and “evil” and rather, what creates resilience and longevity and what does not. When I see the same old narratives continue to explain away humans as “violent” creatures that have “dominated” the planet, I see the same old narratives that got us where we are today. This makes me lose interest more than anything. Through all of this, Sapiens is not a book I would ever ended up reading. But, I gave it a shot and started to read…

The first chapter

My eyes start rolling immediately and I am highlighting narratives and inaccuracies on every page. I am barely able to make it to page four where this cultural-superiority-complex bomb drops:

“On a hike in East Africa 2 million years ago, you might well have encountered a familiar cast of characters: anxious mothers cuddling their babies and clutches of carefree children playing in the mud; temperamental youths chafing against the dictates of society and weary elders who just wanted to be left in peace; chest-thumping machos trying to impress the local beauty and wise old matriarchs who had already seen it all. These archaic humans loved, played, formed close friendships and competed for status and power–but so did chimpanzees, baboons and elephants. There was nothing special about humans. Nobody, least of all humans themselves, had any inkling that their descendants would one day walk on the moon, split the atom, fathom the genetic code, and write history books. The most important thing to know about prehistoric humans is that they were insignificant animals with no more impact in their environments than gorillas, fireflies, or jellyfish.”

This is where I decide that I am not going to waste my time and read this book, no matter how many people recommended it. I continued to read through the first chapter, with equal disdain. Highlighting along the way. It’s a funny coincidence, that his last statement of value in the quoted paragraph above ends with the insignificance of jellyfish. In the novel Ishmael, author Daniel Quinn wrote a parable of the way people in civilization talk about the origins of civilization, as though it is the pinnacle of evolution (evolution has no pinnacle–it’s just life adapting to change, not “progressing” or “devolving”). That the world of humanity was “insignificant” and “nothing special” until a few humans created civilization. However, in this parable, the animal being interviewed by an anthropologist is not a human, and yet they are describing the creation of the world in the same way. At the very end, the animal is revealed to be a jellyfish.

While looking back over this book before posting this review, I saw the very first page I missed something. Before the Table of Contents, before even the title page and copyright page. There is a page that has a quote from the author. The quote is:

“I encourage all of us, whatever our beliefs, to question the basic narratives of our world, to connect past developments with present concerns, and not be afraid of controversial issues.”

This book fails to do this in any meaningful way. I do not recommend it. Instead, I would suggest reading Limited Wants, Unlimited Means edited by John Gowdy.

At last, an intelligent critique of the work of Yuval Noah Harari.

For more (and related), here are a couple of snippets from ‘The Freedom of Things: An Ethnology of Control,’ TSI Press 2017:

In 2013’s The Gap – The Science of What Separates Us from Other Animals, psychology professor Thomas Suddendorf writes: the abandonment of “a hunter-gatherer lifestyle in favour of a sedentary agricultural existence […] enabled rapid population growth and was a catalyst for development. […] Those who have continued to pursue a hunter-gatherer lifestyle have increasingly been marginalized” (Suddendorf: 270). Just the words used here – ‘enabled,’ ‘rapid,’ ‘catalyst,’ and ‘development’ – confer a dynamism on those who have moved on from wild-fooding. These are tropes that confirm the widely accepted benefits of modernity.

The automatic verification of the positive value and, indeed, necessity of these developments is what helps constitute the civilizing discourse, and this sermon is accessed at almost every level and intersection of methodology and logic. Examples of our instinctive reproduction of the civilizing discourse are found riven throughout the arts, sciences and University. Hence, Stephen L. Sass, Emeritus Professor of Materials Science and Engineering at Cornell University, iterates three principles of the civilizing sermon in his book The Substance of Civilization: Materials and Human History from the Stone Age to the Age of Silicon.

Initially, he articulates the notion that humans in their early evolutionary stages were like modern people, civilized people, suddenly appearing in a time where they had to figure out how to manage without modern amenities:

“Early humans faced overwhelming obstacles to survival. They needed food for sustenance, weapons against predators – both animal and human – and shelter from an often brutal environment” (Sass: 15).

Next, he asserts the critical imperative that humanity should move out of primitive existence:

“The transition from a nomadic hunter-gatherer lifestyle to a sedentary existence was crucial and first occurred, so far as we know, in the Near East” (Sass: 23).

And lastly, in his elaboration of the assertion that “Materials guided the course of history” (Sass: 5), he makes the inevitable connection between assumed lower and higher stages of humanity and the tools and materials used:

“Because materials and their uses have evolved, they lead us back to the foundations of human society, and map the movement from a hunter-gatherer style of life toward a more sedentary existence centred around cities. Dense areas of population develop as the materials that foster them become more sophisticated; the denser the population, the more sophisticated the building blocks. So, too, the higher we go literally (airplanes, skyscrapers) the more complex the substances that take us there” (Sass: 7).

Sass would seem to view the progress of humanity as basically consisting of a building-on of previous technologies, or productive capability. This, then, influences the forms of social organization that arise, occurring in some kind of continuous flow, with some reversals of course, for example, Europe’s ‘dark ages.’ This is not so far from how Emeritus Professor of International Relations at Sussex University, Kees van der Pijl, describes the basic premise of Marxist historical materialism: “that all existence is historical, the result of the exploitation of humanity’s relationship with nature, and that social life is therefore destined to change towards novel forms just as it emerged from different relations in the past” (van der Pijl: viii).

Marx and Engels, not coincidentally then, provide a similar narrative to Sass in that they too prioritize technology and production, changes to which inaugurate transformations in the “legal and political superstructures” and in “social consciousness” (Marx 1904: 11), with the difference being that new modes of production emerged from within old ones and they gained ascendency only through rupture and class struggle. Thus, for Marx and Engels, the narrative leading to the civilization we inhabit today is essentially the same, except that they make much more of the bumps in the ride than someone like Sass and, importantly, their compassion compels them to bitter criticism of all societies that enslave and degrade human beings (Sayers: x-xi). Marx and Engels do not ‘support’ what has happened in history in the way that others who see progress as beneficial sometimes appear to do. Rather, they merely claim to describe and expose the process. However, since they see the Industrial Revolution and the bourgeois mode of production as providing, for the first time in history, the basis for a truly rational, enlightened, and communistic mode of production, they do see some value in the long and torturous road (Marx 1976: 173) that humanity has trodden through history, and it is this acknowledgement that gives them away.

…

Historian Yuval Noah Harari in his 2015 book Sapiens: A Brief History of Humankind also offers a narrative of events and developments that exhibit the economic determinism at the heart of Western perspectives. Harari argues that the Agricultural Revolution of around ten thousand years ago occurred not because of a move to sedentary living that eventually led to farming or the rise of powerful elites who were able to force others to work for them, but because of the manipulation of plants such as wheat, rice, and potatoes. The idea is that because humans successfully experimented with growing wheat, his main example, in less wild conditions, the nurturing of wheat became the primary task of nascent human populations. Harari contends that humans lost their easier foraging way of living and became slaves to the cultivation of wheat (Harari: 77-98). Technology, then, alters human desires – everyone wanted wheat – and drives social development.

This methodology is the same as Marx’s, just as Jared Diamond’s theses in Guns, Germs and Steel appear to be “geographic variation in whether, or when, the peoples of different continents became farmers and herders explains to a large extent their subsequent contrasting fates” (Diamond: 86). The strength of the materialist conception of history, of course, lies in the fact that it was not invented by Marx but only revealed in his work as an apparently coherent and effective methodology of critique. Economic determinism is a perspective of the Enlightenment, of a productively sophisticated society that finds the apparent causes of everything in apparently material phenomena. Harari’s seemingly novel idea is, after all, prefigured by Rousseau, who lived before Marx: “For the poet, it is gold and silver; but for the philosopher it is iron and wheat that have civilized men and sealed the fate of the human race” (Rousseau 2011: 75).

People who put forward determinist propositions are often attacked on the assumption that if what humans do is determined by factors beyond their conscious will, then human creativity and free will is potentially sidelined (Diamond: 408). But what is more interesting is that someone like Harari is able to move from an historical materialist or determinist stance on how humans behave and organize themselves – the cultivation of wheat changing everything – to a fixed notion of human behaviour spanning two million years without the blinking of an eyelid. Thus, Harari is able to project back the modern nuclear family, like Sass above, consisting of all its modern traits and characteristics right through all the revolutions in technology and social organization to when humans first appeared on some imagined savannah:

“On a hike in East Africa 2 million years ago, you might well have encountered a familiar cast of human characters: anxious mothers cuddling their babies and clutches of carefree children playing in the mud; temperamental youths chafing against the dictates of society and weary elders who just wanted to be left in peace; chest-thumping machos trying to impress the local beauty and wise old matriarchs who had already seen it all” (Harari: 4).

On the one hand, and irrespective of whether it is correct, Harari puts forth a complex and interesting view in which humans are the product of their environments and the technologies they manipulate. On the other, he advocates the simplistic and sweeping notion that human perceptions and behaviour are essentially static across time, which means that the human being perceived the world, and, therefore, acted within it in the same way in eras as radically diverse as those characterised by, for example, nomadic foraging, feudalism, and industrialism. Can this really be the case? Would the imaginary, presumably twenty-first century person hiking two million years ago really encounter this scene – that could be directly transposed from a family gathering of inhabitants of present-day Los Angeles?

…

[Ludwig Feuerbach (1843) argues:]

[‘Human’] consciousness enables “the capacity to produce systematic knowledge or science” and so, the reflexive consciousness of humans becomes particularly powerful through science, which is “the consciousness of species” (Feuerbach: 98 original emphasis).

However, the development of scientific knowledge has transformed this collective consciousness. The methodology of science has transformed the human “universal being” into a collective being that, as a collective being, possesses unlimited consciousness and unlimited knowledge (Feuerbach: 93, 242). Individual humans are limited in themselves in that no one human can discover or know everything that has been revealed by natural science. But as a universal being, this access is unlimited. That is, individual man has access to all the revelations of science, even if it would be impossible to absorb every single one. This makes the human, as a species-being, essentially capable of “divine knowledge” by which is meant, of course, everything (Feuerbach: 189). It is from this vantage point that Marx and all those who followed, Marxist or otherwise, were able to conclude that people now, with their scientific consciousness, could discover all there was to know about all human societies, including their own. This makes our species-being, our humanness as a collective, for the first time in history, potentially omniscient and omnipresent (Feuerbach: 189-190). In 2011, historian Yuval Noah Harari, in the internationally best-selling Sapiens: A Brief History of Humankind, echoes this notion, though perhaps in cruder terms, when he writes: “Today [humanity] stands on the verge of becoming a god, poised to acquire not only eternal youth, but also the divine abilities of creation and destruction” (Harari: 415).

(‘The Freedom of Things: An Ethnology of Control,’ Peter Harrison, TSI Press 2017)

Thanks for the recommendation. Ordering that book now. Funny how they quoted the same passage from Sapiens! Haha. 😀

“We’re starting to realize that the many different “species” of the Homo genus are most likely just one species: Homo erectus (including us). ”

Huh? Where in the actual fuck did you pull this nonsense out of? No references, no sources, no citations.

I’m an an anthropology PhD candidate and I’ve never read or heard of this before anywhere.

Peter Moss,

Instead of acting in your comment as if your cage has been rattled by a distant sharp wind, why don’t you engage with the proposition, which is elaborated in the text?

Hi Peter Moss,

Indeed, this is a really weird statement unsupported by any references.

I hope Bauer will explain this statement with a bit more evidences and material because it seems really wrong.

Best,

Alexandre

Hi Peter Moss,

I’m enjoying how that one statement is the one from my whole critique that is really ruffling folks feathers. I had a long conversation about all of this a couple years ago with a friend who is also a PhD candidate for paleoanthropology, so it’s obviously not out of the scope of paleoanthropologists in your area. I’ve learned however, since posting this (and will be posting an update), that when a species is already classified, or classified *first,* that it gets preference. So technically speaking, because H. sapiens were classified before H. erectus, I guess we’d all be Homo sapiens. Though, to continue the critique, “Sapiens” means “wise” and I don’t think it’s very “wise” for a particular group of a species to cause a global mass extinction. So, I think I’d just stick with “up right.” 😉 I didn’t cite it, because I honestly didn’t think I needed to. I thought most paleoanthropologists were up on this. Anyway here are some of the references:

• Skull of Homo erectus throws story of human evolution into disarray

https://www.theguardian.com/science/2013/oct/17/skull-homo-erectus-human-evolution?fbclid=IwAR0SJjDVAgULg1DEA-JyDf9EIupWV0Jv8JNbnjh2RM24dcC_RkqhzXDAQpk

• Viewpoint: Human evolution, from tree to braid

https://www.bbc.com/news/science-environment-25559172

• What is the ‘braided stream’ analogy for human evolution?

http://johnhawks.net/weblog/topics/news/finlayson-braided-stream-2013.html?fbclid=IwAR0bpF1zvxB9WLtzTQU9bEH2UlZR_5HxS9DbNjnN3zkIRNQSKeTOptItMXg

• TIME | 4/11 John Hawks – The braided stream: Time and diversity in human origin

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=HzbVxroaO-M

• Human evolution is more a muddy delta than a branching tree

https://aeon.co/ideas/human-evolution-is-more-a-muddy-delta-than-a-branching-tree?fbclid=IwAR2c0BKrrAEk6AmxsZAZgujk-O6cQ08wsS216Ta71PPgzOlrwnv-daWiqvc

• This Face Changes the Human Story. But How?

https://www.nationalgeographic.com/news/2015/09/150910-human-evolution-change/?fbclid=IwAR1-x3gUrGuEIsljSc7IwgRrXHYkMxrem9sNBroE7ucyHjPZGUDLCj5G_t8

• The comparative genomics and complex population history of Papio baboons

https://advances.sciencemag.org/content/5/1/eaau6947?fbclid=IwAR2fmew-Gap3e99ojKH2lkA6Oyd4EvUl0fEiMueIBu49uB2P62SUSFV3afs

Thank you for the reply.

It seems that there are only personal opinions and misconceptions supporting your statement. You have probably misinterpreted the article from The Guardian which is not involving Homo sapiens at all. Homo erectus and Homo sapiens are in the same genus but clearly are not the same species.

The only one I know expressing this weird theory is Rainer Kühne, a very strange person believing in weird stuff about Atlantis.

Best,

Alexandre

All three of us, H. sapiens, denisovans, and neanderthal share DNA from another hominid species that is older than any of us. Sadly, we can’t map H. erectus DNA yet (or ever) because it’s too old. But the theory stands, that if we are all in a lineage flowing in and out of one another (with some dead ends), and you are following the “biological species concept” then we are probably all from that older “species,” which has been theorized to be h. erectus–since we all stemmed from them. Comparing a theory like this, which is backed up by a common dna ancestor, using the biological species concept, to things like atlantis is completely absurd. If you don’t get it, that’s okay. It’s just a theory, but it makes the most sense to me from a biological species concept.

If Homo sapiens, denisovensis and neanderthalensis are descendant from Homo erectus, it is logical they share a part of their DNA with their ancestor. But it does not mean they are from the same species!

Try to apply your reasoning to different species with known ancestors and will end up with a messy classification. Horses share a huge part of their DNA with the other members of the genus Equus and with their common ancestor, it does not mean they are in the same species! And there is gene flow between the different species!

Well articulated Peter! There was a PBS(or was it Nat Geo?) mini series on human origins about 6-12 months(time frame?) ago……I think the word origins was used in the title ?, based on the trailer I anticipated watching it. But they spent all of 15-20 minutes on homo s. time as H/G and went right to beginnings of domestication . So yeah, I share your disappointment with lack of attention/interest in the previous 290 k years. Will the prevalent narrative of civilization ever change while civ still exist…..I guess that’s rhetorical…? Ken

I hate this book too – and these are my specific reasons ~!! 🙂

Objections to “Sapiens” by Yuval Harari :

a) Ethnocentric tone – this is history from a western perspective, it does not take into account the thousands of Indigenous societies that developed successfully OUTSIDE of the model(s) Harari proposes. What about them? There is no such thing as one “HUMANITY” – only western academics have the audacity to continue with this privileged definition and make invisible non-western societies. There are countless cultures outside the rubric of western knowledge who cannot be described by the themes in this book, but does this occur to western academics with PHD’s??? NO – and I am really tired of this implicit racism.

b) Racist comments – Harari decimates the integrity of Indigenous peoples with various insults, plus he conflates the western development timeline with the flourishing of Indigenous societies, which is a complete error. How horrified a First Nations person must be to read this tripe!! For example, this horrible piece of racist bullshit on page 28: “People can easily understand that ‘primitives’ cement their social order by believing in ghosts and spirits, and gathering each full moon to dance around the campfire. What we fail to appreciate is that our modern institutions function on exactly the same basis. Take for example the world of business corporations. Modern business-people and lawyers are in fact, powerful sorcerers. The principle difference between them and tribal shamans is that modern lawyers tall far stranger tales.” THERE IS SO MUCH WRONG WITH THIS PASSAGE I DON’T EVEN KNOW WHERE TO START. Harari has absolutely no knowledge of anthropology and/or the study of indigenous knowledge, Indigenous lifeways, Indigenous peoples and/or Indigenous epistemologies all over the globe, who ironically still carry oral traditions and knowledge through the centuries from the ancient times Harari is describing. Another imperialist error of western academics is to think that living traditions would not hold contradictory or important information to their own thesis.

c) Discounts magic and mystery (which does exist), the numinous (which does exist), the gods and goddesses (which do exist), the earth spirits (which do exist), the divine feminine (which does exist) and all the other ephemeral and metaphysical aspects of both human and other-than-human life on this mysterious and multi-layered planet.

d) Condescendingly includes a brief, shallow and erroneous explanation of animism. Trivializes the capacity of the human being to have transcendental experience, and the need for spiritual expression. Humans are four-fold beings – emotional, rational (mental) physical and spiritual. Like so many western reductionist thinkers, the author only dwells in the realm of the physical and rational, and ignores, pokes fun at, devalues or scorns the human capacity and necessity for the spiritual.

e) Terrible grasp of root causes, engages with a movement or ideology well into its development and then conflates it with things that are not even connected. The worst description of the rise and maintenance of the patriarchy I have ever seen, and his suggested reasons for patriarchal dominance are a complete insult to western women.

f) Better academics and scientists than Harari have determined that Neantherthals went extinct from a naturally-occurring virus or maladaption, not from some kind of “ethnic cleansing” !!! There is evidence of the gene pool being mixed from intimate contact between Neanderthals and other groups, so why would early human-like creatures then slaughter the entire group? Much more accomplished anthropologists and ethnologists than Harari have concluded that Indigenous groups almost NEVER wipe out entire tribes – their focus is on acts of bravery, warrior-to-warrior combat, making a statement, and making off with captives such as women and children to add new blood to the gene pool (who were treated kindly).

g) The megafauna were NOT wiped out by humans, I thought everyone knew that this ridiculous theory has been repeatedly debunked. (See Vine Deloria Jr., archaeologists Todd Surovell, Brigid Grund and many many more. ) The study of contemporaneous Indigenous societies show that they NEVER destroy a species or food source to the point of extinction, but remain WITHIN the carrying capacity of the land. The plant or animal species is ALWAYS left with a colony or colonies to re-propagate itself. There has NEVER been an instance of indigenous peoples wiping out an entire species, unlike European or western groups who have no problem with mass and total annihilation. As western thinkers support ethnocide and genocide so readily, this theory appears over and over through the western lens. How absurd that if Indigenous groups today (and let’s say the past 800 years ) did not practice ecocide, why in the world would our most ancient forebears practice it? Habitation on the planet was only getting going!!! That small scattered groups of hunter–gatherers could kill entire gigantic species is a ridiculous notion, and those who subscribe to it seriously misguided.

h) This is such an important point – even the title says it all – “A Brief History of Humankind.” Some people have never followed the civilizational impulse, and this title invisibilizes them. I come across this ALL THE TIME – when white authors have the audacity to speak of “humanity” when they are only describing the white POV, western knowledge systems, and the world as seen through a western lens. ABSOLUTELY, there are countless cultures outside the rubric of western knowledge systems who have NEVER lost their connection to the Earth, but this does not occur to white people with PHD’s, and I am really really tired of this implicit racism.

Like a grammar nazi, all I see here is Mr. Bauer being a PhD nazi.

Hariri is writing this book for the layman. The layman is drawn to the title, whereas an anthropologist is going to be like, “Duh, sapiens are humans, dumbass.”

From then on Mr Bauer goes on to make some conspiratorial assumptions about what the author ‘really’ means.

And Pegi Eyers, Hariri is an athiest and athiests do exist. Get over it.